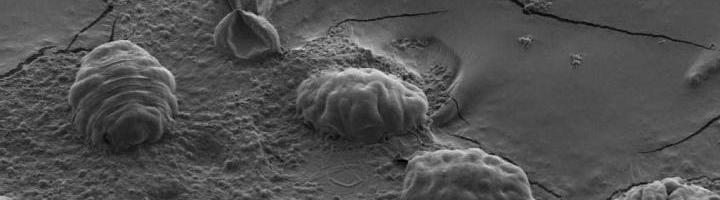

A scanning electron micrograph of 6 tardigrades in their tun state. When tardigrades dry out, they retract their legs and heads within their cuticle, forming a ball-like ‘tun.’ (Image by T.C. Boothby)

Tardigrades are among the most resilient species on the planet: they can survive in the deep sea, in nearly-absolute zero temperatures, and even in space. Also known as water bears or moss piglets, their survival in the most extreme of conditions has been mind-boggling for generations of scientists. Now, researchers believed they have solved a piece of that puzzle by discovering a mechanism that keeps tardigrades from drying out: a unique set of proteins called tardigrade-specific intrinsically disordered proteins (TDPs). These proteins seem to “turn on” whenever a tardigrade begins to dry out. This helps the animals form glass-like protective solids instead of crystallizing, which would lead to desiccation.

Authors:

Thomas C. Boothby, Hugo Tapia, Alexandra H. Brozena, Samantha Piszkiewicz, Austin E. Smith, Ilaria Giovannini, Lorena Rebecchi, Gary J. Pielak, Doug Koshland, Bob Goldstein

Corresponding author:

Thomas C. Boothby, Life Sciences Research Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of Chemistry, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Email: tboothby@gmail.com

Original paper published in Molecular Cell on March 16, 2017.